Thành viên:ChopinChemist/Cường độ (âm nhạc)

Trong âm nhạc, cường độ hay biến cường của một bản nhạc là sự thay đổi về âm lượng giữa các nốt nhạc hoặc phân câu. Cường độ được chỉ định bằng các ký âm cụ thể, thường được thêm một số chi tiết. Tuy nhiên, các ký hiệu cường độ yêu cầu người biểu diễn phải diễn giải tùy thuộc vào bối cảnh âm nhạc: một ký hiệu cụ thể có thể tương ứng với âm lượng khác nhau giữa các bản nhạc hoặc thậm chí các phần của một bản nhạc. Việc thể hiện cường độ cũng mở rộng ra ngoài phạm vi âm lượng để bao gồm cả những thay đổi về âm sắc và đôi khi là tempo rubato.

Dấu cường độ

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]| Name | Letters | Level |

|---|---|---|

fortississimo

|

fff | cực mạnh |

fortissimo

|

ff | rất mạnh |

forte

|

f | mạnh |

mezzo-forte

|

mf | mạnh vừa |

mezzo-piano

|

mp | nhẹ vừa |

piano

|

p | nhẹ |

pianissimo

|

pp | rất nhẹ |

pianississimo

|

ppp | cực nhẹ |

The two basic dynamic indications in music are

Hai ký hiệu chỉ cường độ cơ bản trong âm nhạc là:[2]

More subtle degrees of loudness or softness are indicated by:

- mp, thay cho mezzo-piano, nghĩa là "nhẹ vừa".

- mf, thay cho mezzo-forte, nghĩa là "mạnh vừa".

- più p, thay cho più piano, nghĩa là "nhẹ hơn".

- più f, thay cho più forte, nghĩa là "mạnh hơn".

Việc sử dụng ba chữ f hoặc p liên tiếp cũng thường thấy:

- pp, thay cho pianissimo, nghĩa là "rất nhẹ".

- ff, thay cho fortissimo, nghĩa là "rất mạnh".

- ppp ("ba piano"), thay cho pianississimo hoặc piano pianissimo, nghĩa là "cực nhẹ".

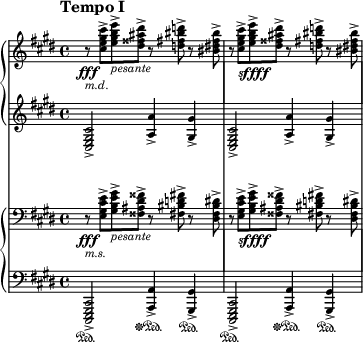

- fff ("ba forte"), thay cho fortississimo hoặc forte fortissimo, nghĩa là "cực mạnh".[4][2]

There are additional special markings that are not very common:

- sfz hoặc sf, thay cho sforzando và nghĩa là "mạnh đột ngột", which only applies to a given beat.

- rfz hoặc rf, thay cho rinforzando và nghĩa là "tăng cường", which refers to a sudden increase in volume that only applies to a given phrase.

- n hoặc ø, thay cho niente và nghĩa là "không còn gì", which refers to silence; it is generally used in combination with other markings for special effect.

Thay đổi

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

Three Italian words are used to show gradual changes in volume:

- crescendo (abbreviated cresc.) translates as "increasing" (literally "growing")

- decrescendo (abbreviated to decresc.) translates as "decreasing".

- diminuendo (abbreviated dim.) translates as "diminishing".

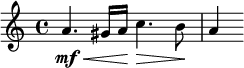

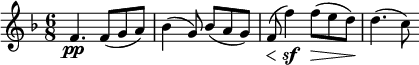

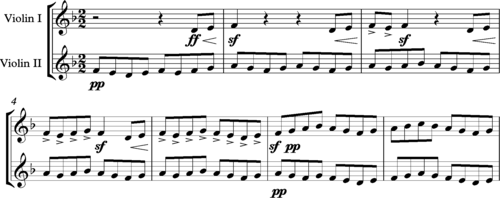

Dynamic changes can be indicated by angled symbols. A crescendo symbol consists of two lines that open to the right (![]() ); a decrescendo symbol starts open on the left and closes toward the right (

); a decrescendo symbol starts open on the left and closes toward the right (![]() ). These symbols are sometimes referred to as hairpins or wedges.[5] The following notation indicates music starting moderately strong, then becoming gradually stronger and then gradually quieter:

). These symbols are sometimes referred to as hairpins or wedges.[5] The following notation indicates music starting moderately strong, then becoming gradually stronger and then gradually quieter:

Hairpins are typically positioned below the staff (or between the two staves in a grand staff), though they may appear above, especially in vocal music or when a single performer plays multiple melody lines. They denote dynamic changes over a short duration (up to a few bars), whereas cresc., decresc., and dim. signify more gradual changes. Word directions can be extended with dashes to indicate the temporal span of the change, which can extend across multiple pages. The term morendo ("dying") may also denote a gradual reduction in both dynamics and tempo.

For pronounced dynamic shifts, cresc. molto and dim. molto are commonly used, with molto meaning "much". Conversely, poco cresc. and poco dim. indicate gentler changes, with "poco" translating to a little, or alternatively poco a poco meaning "little by little".

Sudden dynamic changes are often indicated by prefixing or suffixing subito (meaning "suddenly") to the new dynamic notation. Subito piano (abbreviated as sub. p or p sub.) ("suddenly soft") implies a quick, almost abrupt reduction in volume to around the p range, often employed to subvert listener expectations, signaling a more intimate expression. Likewise, subito can mark sudden increases in volume, as in sub. f or f sub.) ("suddenly loud").

Accented notes are generally marked with an accent sign > placed above or below the note, emphasizing the attack relative to the prevailing dynamics. A sharper and briefer emphasis is denoted with a marcato mark ^ above the note. If a specific emphasis is required, variations of forzando/forzato, or fortepiano can be used.

forzando/forzato signifies a forceful accent, abbreviated as fz. To enhance the effect, subito often precedes it as sfz (subito forzato/forzando, sforzando/sforzato). The interpretation and execution of these markings are at the performer's discretion, with forzato/forzando typically seen as a variation of marcato and subito forzando/forzato as a marcato with added tenuto.[6]

The fortepiano notation fp denotes a forte followed immediately by piano. Contrastingly, pf abbreviates poco forte, translating to "a little loud", but according to Brahms, implies a forte character with a piano sound, although rarely used due to potential confusion with pianoforte.[7]

Messa di voce is a singing technique and musical ornament on a single pitch while executing a crescendo and diminuendo.

Extreme dynamic markings

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]

While the typical range of dynamic markings is from ppp to fff, some pieces use additional markings of further emphasis. Extreme dynamic markings imply either a very large dynamic range or very small differences of loudness within a normal range. This kind of usage is most common in orchestral works from the late 19th century onward. Generally, these markings are supported by the orchestration of the work, with heavy forte passages brought to life by having many loud instruments like brass and percussion playing at once.

- In Holst's The Planets, ffff occurs twice in "Mars" and once in "Uranus", often punctuated by organ.[8]

- In Stravinsky's The Firebird Suite, ffff is marked for the strings and woodwinds at the end of the Finale.

- Tchaikovsky marks a bassoon solo pppppp (6 ps) in his Pathétique Symphony[9] and uses ffff in passages of his 1812 Overture[10] and his Fifth Symphony.[11] [12]

- The baritone passage "Era la notte" from Verdi's opera Otello uses pppp, though the same spot is marked ppp in the full score.[13]

- Sergei Rachmaninoff uses sffff in his Prelude in C♯, Op. 3 No. 2.[14]

- Gustav Mahler, in the third movement of his Seventh Symphony, gives the celli and basses a marking of fffff (5 fs), along with a footnote directing 'pluck so hard that the strings hit the wood'.[a][15]

- On the other extreme, Carl Nielsen, in the second movement of his Fifth Symphony, marked a passage for woodwinds a diminuendo to ppppp (5 ps).[16]΄

- Brian Ferneyhough, in his Lemma-Icon-Epigram, uses ffffff (6 fs).[17]

- Giuseppe Verdi, in Scene 5 (Act II from his opera Otello), uses ppppppp (7 ps).[18]

- György Ligeti uses extreme dynamics in his music: the Cello Concerto begins with a passage marked pppppppp (8 ps),[19] in his Piano Études Étude No. 9 (Vertige) ends with a diminuendo to pppppppp (8 ps),[20] while Étude No. 13 (L'Escalier du Diable) contains a passage marked ffffff (6 fs) that progresses to a ffffffff (8 fs)[21] and his opera Le Grand Macabre has ffffffffff (10 fs) with a stroke of the hammer.

History

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]On Music, one of the Moralia attributed to the philosopher Plutarch in the first century AD, suggests that ancient Greek musical performance included dynamic transitions – though dynamics receive far less attention in the text than does rhythm or harmony.

The Renaissance composer Giovanni Gabrieli was one of the first to indicate dynamics in music notation. However, much of the use of dynamics in early Baroque music remained implicit and was achieved through a practice called raddoppio ("doubling") and later ripieno ("filling"), which consisted of creating a contrast between a small number of elements and then a larger number of elements (usually in a ratio of 2:1 or more) to increase the mass of sound. This practice was pivotal to the structuring of instrumental forms such as the concerto grosso and the solo concerto, where a few or one instrument, supported by harmonic basso continuo instruments (organ, lute, theorbo, harpsichord, lirone, and low register strings, such as cello or viola da gamba, often used together) variously alternate or join to create greater contrasts. This practice is usually called terraced dynamics, i.e. the alternation of piano and forte.

Later baroque musicians, such as Antonio Vivaldi, tended to use more varied dynamics. J.S. Bach used some dynamic terms, including forte, piano, più piano, and pianissimo (although written out as full words), and in some cases it may be that ppp was considered to mean pianissimo in this period. In 1752, Johann Joachim Quantz wrote that "Light and shade must be constantly introduced ... by the incessant interchange of loud and soft."[22] In addition to this, the harpsichord in fact becomes louder or softer depending on the thickness of the musical texture (four notes are louder than two).

In the Romantic period, composers greatly expanded the vocabulary for describing dynamic changes in their scores. Where Haydn and Mozart specified six levels (pp to ff), Beethoven used also ppp and fff (the latter less frequently), and Brahms used a range of terms to describe the dynamics he wanted. In the slow movement of Brahms's trio for violin, horn and piano (Opus 40), he uses the expressions ppp, molto piano, and quasi niente to express different qualities of quiet. Many Romantic and later composers added più p and più f, making for a total of ten levels between ppp and fff.

An example of how effective contrasting dynamics can be may be found in the overture to Smetana’s opera The Bartered Bride. The fast scurrying quavers played pianissimo by the second violins form a sharply differentiated background to the incisive thematic statement played fortissimo by the firsts.

Relation to audio dynamics

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]The introduction of modern recording techniques has provided alternative ways to control the dynamics of music. Dynamic range compression is used to control the dynamic range of a recording, or a single instrument. This can affect loudness variations, both at the micro-[23] and macro scale.[24] In many contexts, the meaning of the term dynamics is therefore not immediately clear. To distinguish between the different aspects of dynamics, the term performed dynamics can be used to refer to the aspects of music dynamics that is controlled exclusively by the performer.[25]

Xem thêm

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]Ghi chú

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]- ^ So stark anreißen, daß die Saiten an das Holz anschlagen.

Tham khảo

[sửa | sửa mã nguồn]- ^ Read, Gardner (1969/1979). Music Notation: A Manual of Modern Practice, p.250. 2nd edition. Crescendo Publishing, part of Taplinger Publishing. ISBN 0-8008-5453-5.

- ^ a b c d Nguyễn Bách (2021). Từ điển Giải thích Thuật ngữ âm nhạc. Tân Bình, Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh: Nhà xuất bản Tổng hợp Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh. tr. 62. ISBN 978-604-335-342-6.

- ^ a b Randel, Don Michael (2003). The Harvard Dictionary of Music (ấn bản thứ 4). Cambridge, MA, US: Harvard University Press Reference Library.

- ^ “Dynamics”. Virginia Tech Multimedia Music Dictionary. Bản gốc lưu trữ ngày 7 tháng 4 năm 2014. Truy cập ngày 19 tháng 3 năm 2012.

- ^ Kennedy, Michael and Bourne, Joyce: The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Music (1996), entry "Hairpins".

- ^ Gerou, Tom; Lusk, Linda (1996). Essential Dictionary of Music Notation: The Most Practical and Concise Source for Music Notation. Van Nuys, CA: Alfred Music Publishing. tr. 37–38. ISBN 978-0882847306.

- ^ An Enigmatic Marking Explained, by Jeffrey Solow, Violoncello Society Newsletter, Spring 2000

- ^ Holst, Gustav (1921). The Planets. London: Goodwin & Tabb. tr. 29, 42, 159. Truy cập ngày 11 tháng 2 năm 2023.

- ^ Tchaikovsky, Peter Ilyitch (1979). Fourth, Fifth and Sixth Symphonies in Full Score. New York: Dover Publications. First movement, just before Allegro vivo. ISBN 048623861X. OCLC 6414366.

- ^ Nikolayev, Aleksandr (biên tập). P.I. Tchaikovsky: Complete Collected Works, Vol. 25. tr. 79. Truy cập ngày 11 tháng 2 năm 2023.

- ^ Tchaikovsky, Peter Ilyich (1979). Fourth, Fifth and Sixth Symphonies in Full Score. New York: Dover Publications. tr. 18, 65 [on PDF]. ISBN 048623861X. OCLC 6414366.

- ^ See imslp- p.88, Andante non tanto.

- ^ (1965). The Musical Times, Vol. 106. Novello.

- ^ Rachmaninoff, Sergei (1911). Thümer, Otto Gustav (biên tập). Album Book I. Op. 3, Nos. 1–5. London: Augener. tr. 5. Truy cập ngày 11 tháng 2 năm 2023.

- ^ Mahler, Gustav (1909). Symphonie No. 7. Leipzig: Eulenburg. tr. 229. Truy cập ngày 11 tháng 2 năm 2023.

- ^ Nielsen, Carl. Fjeldsøe, Michael (biên tập). Vaerker, Series II, No.5. tr. 128. Truy cập ngày 11 tháng 2 năm 2023.

- ^ Ferneyhough, Brian (1982). Lemma-Icon-Epigram. London: Edition Peters 7233.

- ^ “Extremes of Conventional Music Notation”.

- ^ Kirzinger, Robert. “György Ligeti – Cello Concerto”. allmusic. Truy cập ngày 12 tháng 12 năm 2018.

- ^ “György Ligeti – Études for Piano (Book 2), No. 9 [3/9]”. YouTube. 6 tháng 4 năm 2015. Sự kiện xảy ra vào lúc 3:34. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 2 tháng 11 năm 2021. Truy cập ngày 26 tháng 4 năm 2018.

- ^ “György Ligeti – Études for Piano (Book 2), No. 13 [7/9]”. YouTube. 2 tháng 9 năm 2015. Sự kiện xảy ra vào lúc 5:12–5:14. Lưu trữ bản gốc ngày 2 tháng 11 năm 2021. Truy cập ngày 26 tháng 4 năm 2018.

- ^ Donington, Robert: Baroque Music (1982) WW Norton, 1982. ISBN 0-393-30052-8. Page 33.

- ^ Katz, Robert (2002). Mastering Audio. Amsterdam: Boston. tr. 109. ISBN 0-240-80545-3.

- ^ Deruty, Emmanuel (tháng 9 năm 2011). “'Dynamic Range' & The Loudness War”. Sound on Sound. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 1 năm 2018.

- ^ Elowsson, Anders; Friberg, Anders (2017). “Predicting the perception of performed dynamics in music audio with ensemble learning” (PDF). The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 141 (3): 2224–2242. Bibcode:2017ASAJ..141.2224E. doi:10.1121/1.4978245. PMID 28372147. Bản gốc (PDF) lưu trữ ngày 17 tháng 1 năm 2018. Truy cập ngày 16 tháng 1 năm 2018.

Bản mẫu:Dynamics (music) Bản mẫu:Musical notation Bản mẫu:Musical technique